Horror Games Don’t Exist, Video Games Are Lying To You

Something has been on my mind lately. A thought I cannot escape nor put to rest, haunting me like a vengeful specter. A thought that keeps me up into the night, wondering how to make sense of such eldritch awareness. A thought that, like a curse, I shall cast upon all who read this, forever changing them for the worse.

Horror games don’t exist.

There is no such thing as a “horror game”. There just isn’t, and any games that claim to be “horror games” are lying to you. This is not to say video games cannot use horror or inflict it upon their players, but games simply cannot describe themselves as “horror” from a genre standpoint. At least, not in the way that other types of media can.

See, despite what it may sound like, I do respect the genres of media. I believe film, for instance, rides or dies these days on genre - just look at the popularity of the Superhero genre for a clear example - but unlike games, literally every other form of entertainment media has only one way it can achieve its goals in engrossing its viewer: by conveying to them a satisfying story. As such, the genres of these stories primarily refer to their subject matter, and it’s these genres that do most of the legwork to attract an audience. Does the audience want a romance story? An action story? A science-fiction story? Whatever the story is, the genre helps lure them in by acting as a clear indicator of the type of story to expect.

But games are just different. Their audiences engage with them in a different way than a movie, a book, or a song - unique to games, the player is an active participant in the piece. Because of this, while the narrative trappings of a game can do some of the dirty work to attract players, what matters more in the end is how the game actually plays. As such, the medium of games has developed its own subset of genres over its lifespan that are based on how you interact with them rather than their themes or stories. These usually come with such snappy names too, like “first-person shooters”, “metroidvanias”, or “role-playing games” (which is a phrase I have all sorts of qualms with but that’s a rant for another day). That’s the lovely thing about these names; once you’re familiar with the terminology, they can give you a pretty clear idea of what a game will play like when they’re attached to a product.

Except for horror games.

Somehow, the genre of “horror” has slithered through the cracks of cinema and into the world of gaming, and it irks me something fierce. Now don’t get me wrong - gaming is great for horror experiences. The unique interactivity games offer makes them arguably more effective at scaring an audience than any other medium, since the player is a direct part of the game. But that’s just the thing - there’s nothing interactive about calling a game a “horror game”. Describing a game as a “horror” game is like calling one a “science-fiction” game - it means basically nothing for the game itself. Seriously, think about it - what defines a “horror” game? That it scares the player? Pokemon: Diamond and Pearl are horror games. Don’t believe me? Check out the Old Chateau area with the lights off and come back to me. Case in point, the horror genre means nothing to games! It’s just a layover from film that says the game might be scary! Horror is literally just a premise, a vibe even, not a genre of game! Hell, because the term is so loose, “horror games” can be all sorts of actual gaming genres. Here, would it help if I gave you some examples?

Resident Evil 2 (2019), Capcom

Pictured above is a screenshot from the remake of Resident Evil 2, released in 2019, 21 years after the original Playstation game. The original version was a genre-defining experience in which the player solved puzzles, rationed resources, and explored a barricaded police station during a zombie outbreak in search of a way out. While the monsters that lurk in the Raccoon City Police Department are indeed scary (those sewer monsters in particular are the stuff of nightmares), the game’s standout horror comes from a direct connection between the player’s choices and the survival of their character. Since scouring the police station can only provide so much in the way of supplies, players are essentially always deciding how to ration what resources they can carry, be it medicine, bullets, or even key items for solving puzzles, which masterfully creates a sensation of tension that teeters on the brink of abject terror at nearly all times. Personally, the 2019 remake is one of the best games ever made; it updates the experience of the original to modern design sensibilities (goodbye, tank controls!) without losing what made it so iconic.

Doki Doki Literature Club (2017), Team Salvato

Now pictured above is a game called Doki Doki Literature Club, a much smaller game from 2017. The game is something of a satire of the visual novel genre, beginning as a relatively played-straight story about a high school boy joining a club with a small cast of cute girls to flirt with, only to suddenly shift into a horror story as one of the characters reveals her meta-narrative control over the game itself and its setting, which she uses to torture or kill the rest of the cast and flirt not with the player’s avatar, but the actual human being beyond the screen. Being a visual novel, the player is extremely limited in how they interact with the game, only being able to make occasional dialogue choices and decisions that veer the story down slightly different routes. That is, up until the end, at which point (spoilers) the player must wrench control of the narrative from Monika by literally deleting her character files from the game’s cache. I’ve always felt like the game was a triumph of a game that takes full advantage of its medium, using its existence as a video game (and the existing tropes of its genre as an anime-girl-dating-simulator) to unsettle players in ways no other medium can.

But seriously, what do these two games have in common besides being labeled as “horror games”? The answer is practically nothing. One is an action-packed survival experience, and the other is a meta-satire visual novel with bare minimum player input. They couldn’t be more different, yet they are bunched together because they both aim to scare their players first and foremost, and I find that ridiculous. Under no circumstances are these two games the same genre - hell, there are other so-called “horror” games that shouldn’t be in the same conversation as them either. Games like Dead by Daylight (an asymmetrical multiplayer game), Fear & Hunger (a turn-based RPG), and The Mortuary Assistant (a job simulator that’ll scare the pants off of you). The umbrella of “horror” games stands over a laundry list of games that come in all shapes and sizes, far beyond any of its other contemporary genres, and because of this, one overarching "horror game genre” is essentially meaningless. “Horror games” can be anything, and therefore horror games do not exist. Any game that says it is simply a “horror game” is lying to you, because it is always something else on top of being scary in theme or premise.

And this is what makes horror games awesome.

Sweet Home (1989), Capcom

Because the “horror” game genre doesn’t exist, a “horror game” comes with no conventions, no requisite mechanics, no pre-established understanding of what the game must play like. This is unlike literally any contemporary video game genre - a first-person shooter will have you shooting enemies with some sort of weapon, a role-playing game (again, name aside) will usually involve strategic battles and balancing numerical stats, and a platformer game will involve traversing obstacle courses in some way. Horror games don’t have any of that; they are free from the chains that bind any other genre, which allows them to be whatever they want.

Take Sweet Home for instance. Inspired by a film of the same name, the game was developed by Capcom and released in 1989 for the Famicom, never being officially released outside of Japan. The game is the precursor to Resident Evil, which was even initially planned to be a remake of its predecessor. It has a familiar premise - a group of filmmakers trespass into an abandoned mansion looking for riches and encounter supernatural threats within - but in a manner most would consider bizarre compared to today’s “horror” games, Sweet Home is a turn-based RPG in the style of Dragon Quest or Final Fantasy, with top-down maps and random enemy encounters. While it did establish many of the traditions the Resident Evil games would carry forward into the future, its choice of gameplay genre makes it completely alien to a modern gamer (or at least someone who hasn’t heard of Fear & Hunger, which in some ways is a good thing). How Sweet Home generates horror is through its encounters and lethality - while you explore the game’s setting, not only will you be beset upon by a cast of freaky monsters meant to unnerve you, but also random traps and events that work like a proto-quicktime event, forcing you to choose a maneuver to dodge the threat. These can be all sorts of traps like flying swords, falling chandeliers, or pitfalls in the floor. What’s more, if one of your five characters perishes, there is no way to get them back; no churches or phoenix downs here. For an extremely early attempt at horror in video games, it works surprisingly well, especially for such a unique genre.

Another good example of the fluidity of horror in video games is the Five Nights at Freddy’s series. This franchise is proof that not only can horror games be so different from one another, horror games in the same series can be just as diverse due to the lack of genre definition. It’s hard to describe the first four games as anything besides “job simulators”; they usually consist of being constrained to an office or equivalent room, managing some kind of life-supporting resource like power or oxygen while you keep a lookout for threats trying to break into your room and kill you. This in and of itself is a pretty great source of horror, forcing players into stressful scenarios where their execution skills are all that stands between them and a gruesome death at the hands of a killer Chuck-E-Cheese ripoff. Otherwise, the series relies heavily on atmosphere to sell its scares (something I personally believe they have only gotten worse at over time). After those four games though, the series takes a huge departure from its established expectations. A point-and-click adventure game with no proper recurring mechanics between nights, two VR minigame collections, and now a first-person exploration game with metroidvania elements have all been added to the franchise’s catalogue, among others. If anything, the FNAF series alone is proof that horror games really don’t have any real gameplay conventions.

Catherine: Full Body (2019), Atlus & SEGA

One particularly weird game I want to bring up, which I think shows just how bizarre horror games get to be without specified conventions, is a game called Catherine. The game is extremely far removed from the landscape of other horror games, to the point that one might argue it might not even be a horror game at all, but I’d disagree. Hell, it seems the game’s reviews on Steam agree with me, since it carries the user-defined Horror tag on its store page, voted onto it by other players. Catherine makes for perhaps the perfect example of just how unique a “horror” game can be. Both it and its rerelease Catherine: Full Body are about a man named Vincent who must traverse his shaky relationship with his long-term girlfriend after he cheats on her with a girl with the same name (albeit spelled with a C rather instead of a K). Gameplay-wise, Catherine is a horror game with not one gameplay genre, but two: by day, players control Vincent’s social life like a life-sim, altering his relationships with his friends and lovers, and by night, the game becomes a puzzle-platformer about moving blocks around to climb a nightmarish tower and escape from abstract monsters inspired by the tribulations of Vincent’s love life. Despite it’s aesthetic resembling Atlus’ catalogue of JRPGs, the game is still firmly a horror story, just not a monster or slasher story like most of the other games I’ve brought up today. It’s a little closer to Fatal Attraction with a supernatural, David Lynch-ian twist (a twist Atlus seems to be a big fan of). I just love this game in comparison to other horror games for how unique it is from such an already-diverse crowd. Even though it’s trying to tell a compelling story, it’s not afraid to have extremely crunchy, skill-based gameplay that still abstractly draws from and compliments it themes and narrative. It doesn’t rely on jumpscares or making the player feel helpless to be scary - if anything, running out of doable actions, especially during the puzzles, is considered a fail-state - and the overall vibe of the game is way more suave and appealing than horror games usually are thanks to its funky soundtrack and anime style.

Now, there’s a detail I’ve been dancing over this whole time. I’m sure that, if I were to say all of this directly to someone’s face (and assuming they listen to me to the end), I’m sure to be asked “Hey Sam, what about survival horror games? That’s a genre with actual gameplay conventions!” And while I can’t argue with that, survival horror games have always been assumed to be a sub-genre of “horror games”, but that grants it some special privileges that a much broader genre doesn’t have. Survival horror games are indeed a real genre with some clear conventions attached to it, but that’s the thing - the survival part is carrying a lot of that weight, while the horror part is just the genre that is being reinterpreted through the first half of the title, more like a direction than an active part of the game genre. What I mean by this is that the game’s mechanics are survival-oriented (things like gathering resources and making decisions or plans on when to spend them) while the horror aspect influences how the system is designed (inducing terror in players by creating tense situations, often by limiting the abundance or accessibility of resources or putting players in situations where they need to expend more resources than they would otherwise want to). There are absolutely survival games that are not survival horror games. Take Raft for instance, a game by Redbeet Interactive. The game is definitely a survival game, but not a survival horror game. In it, you gather materials and supplies from the ocean to upgrade your floating vessel which you use to keep yourself alive, craft new tools, and explore key points across the game’s world. Hazards like sharks and such are present, but are never such dire threats that players are shaking in their boots when faced with them (unless you’re thalassaphobic, I guess). Highly efficient or driven players can eventually reach a state where they hardly need to worry about their resources, with rafts that passively gather or grow new supplies for them while they focus on other things. In a way, the game can feel very zen once you reach that point.

Amnesia: The Bunker (2023), Frictional Games

Meanwhile, Frictional Games’ Amnesia: The Bunker is a survival horror game. That’s a game where your resources are always scant and safety is in short supply, the environment is dark and foreboding, and every venture into the game’s sprawling military trench setting requires forethought to avoid being mauled to death by whatever lurks in the shadows. Its horror direction is truly something to be admired, especially as an evolution of Amnesia: The Dark Descent, which was so influential on horror games that I’d be willing to coin its own sub-genre of imitators as “amnesia-clones”. You’re in a constant state of tension, weighing your options and coming up with plans and routes to avoid confrontations and make as best use of the tools at your disposal as you can. One thing that’s special about the game is it even gives you a revolver, which makes sense since you play as a soldier neck-deep in the bloody conflict of World War 1. However, it’s hardly meant to be used as a reliable weapon against foes; instead, its primary uses are for dealing with small threats like packs of rats or to detonate explosives from afar, or god forbid, scare off the hulking “Beast” that stalks the bunker’s crumbling halls. Bullets are so rare to find, though, that you’ll almost never have a full cylinder of them, making each shot fired a conscious decision to expend one of your almighty bullets. Shooting the gun frequently is hardly recommended anyway, as doing so is so loud it will snuff out the game’s audio as your character’s ears ring, and if the Beast didn’t know your location before, it certainly does now.

I should mention that there exist other more concrete sub-genres of “horror”, too. Each of these sub-genres, like survival horror before them, manage to do the one thing that the horror “genre” doesn’t - actually integrate defined, overarching gameplay mechanics or directions. I brought up “amnesia-clones” a second ago, a genre I would say is defined by the player’s inability to fight back against monsters and is usually full of logic puzzles to solve. Games like Still Wakes the Deep, SOMA, and Alien: Isolation apply here, even despite the latter having a considerable amount of combat outside of dealing with a goddamn xenomorph on your tail. Speaking of which, “action horror” games also exist, such as the original Alan Wake and Dead Space, in which players are doing just as much shooting with diverse and satisfying weapons as they are feeling scared shitless by frightening foes or scenarios. Many would even agree Dead Space 3 veers too far into action, losing much of the horror the games were known for along the way. “Horror platformers” are also bizarrely common, with games such as Little Nightmares or Outside fitting the bill as games primarily about moving through obstacle course-like environments to avoid horrible monsters in spooky environments.

So yeah - there’s not really a such thing as a simple “horror game”, which has led the horror genre to become the most diverse and unique genre of them all. Horror games get to be a lot more freeform than any other type of game; Their gameplay conventions are nonexistent, so a developer can put horror trappings over basically any other genre, or perhaps a game without a clear genre at all, and call it a “horror game”. It allows for so many unique and interesting experiences to come out of the horror scene for games, and permits some truly creative and weird ideas to shine. All it really takes is a compelling, immersive idea and some solid direction to make a horror game, gameplay genre be damned. I mean, I’m sure someone can make a truly terrifying crossword puzzle if they tried hard enough. Hell, my contact info is up on the top bar - if you know of any, or even any other really unique or cool horror games, please let me know!

…

Oh, you’re still here? What, are you expecting a jumpscare if you scroll down far enough? Well, sorry pal, as much as I love a good meta scare, I wouldn’t want to turn this blog post into a copycat of Bonngcheon-Don Ghost. But what I can give you is one last game recommendation, for what I firmly believe is gaming’s best up-and-coming horror experience in years. A game that is, at least to me, one of the most interesting games I’ve ever seen, and yet another genre-defying “horror” game that stands apart from the rest. And this time around, I won’t be spoiling anything about it. To do so would to do the game a disservice, because it’s all about the unknown.

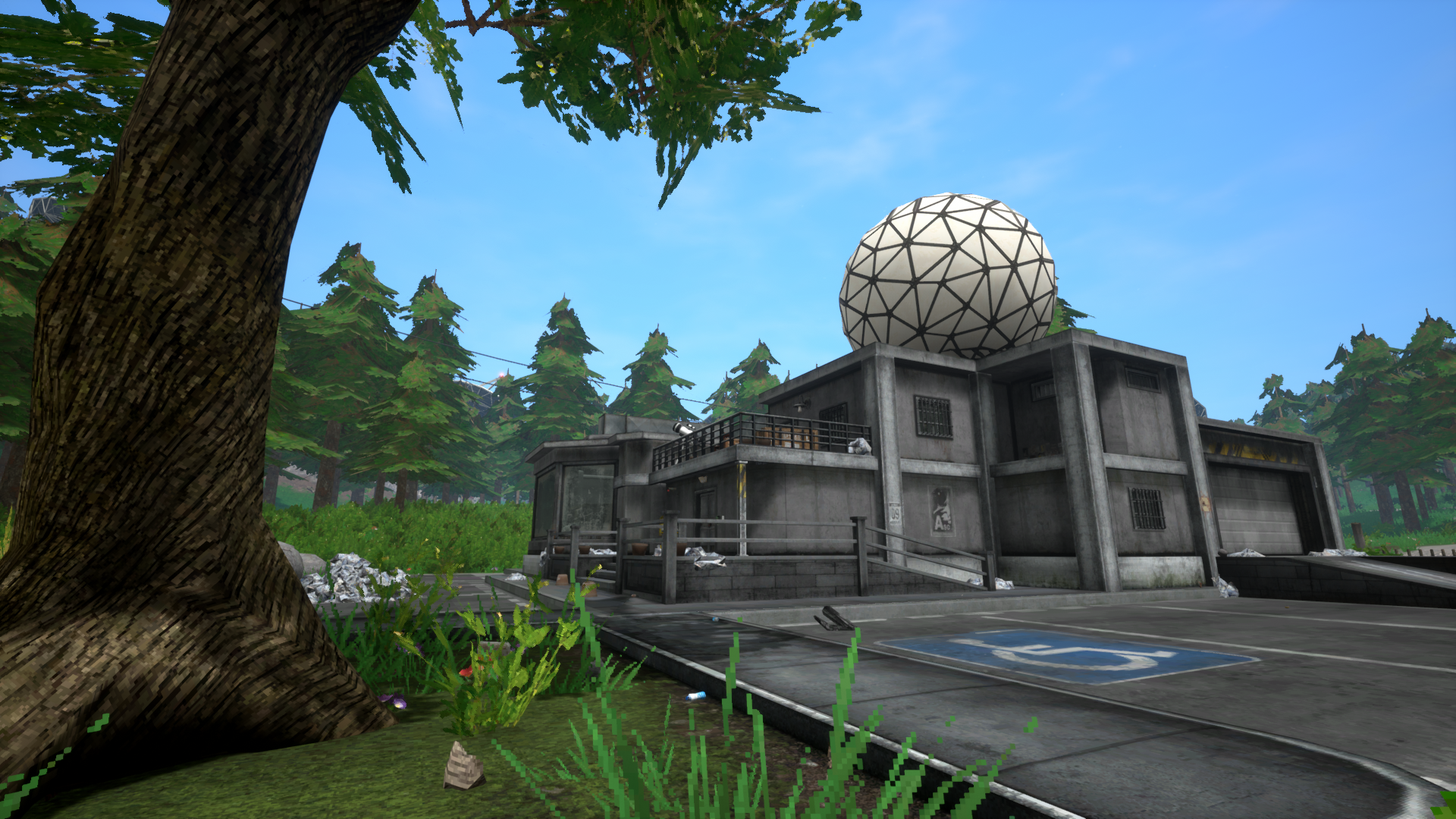

Voices of the Void (2022 - ongoing), mrdrnose

The game is called Voices of the Void. You can find it here at mrdrnose’s itch.io page for whatever price you want. The game is a “horror” game, but its horror is almost entirely up to the player’s level of interaction and curiosity; It knows that all it takes for the game to generate horror is to face the player with the unknown - after that, the player themselves can take it from there.

Voices of the Void is a job simulator and sandbox game of sorts. You play as a lone scientist running a satellite farm in the remote Swiss countryside, searching for signals from outer space. Your days will usually consist of a handful of menial tasks for your job - tracking signals, up-keeping your base, eating and sleeping to survive - and the game has this really lonely-but-comfy vibe where it's just you in the distant wilderness with minimal outside contact. There's a lot of stuff you can find or buy to spruce up your base and really make it feel like a home, the map is expansive and full of secrets to discover, and a lot of the game is about improving your routine to do your job more optimally, which feels very satisfying.

But every once in a while… weird things happen. Things that will make you question if you're really alone on the premises, or worse, if you're even safe. The base is more than just your home - it's your fortress against the unknown, either from outer space or much closer. And no matter what bizarre or frightening things happen, you still have a job that your boss expects you to get done. Perhaps, if your schedule allows, you can go investigating the things that go bump in the night for yourself and do some real mystery solving. Who knows what you might uncover…

I wish I could say more, but I’d never want to spoil the secrets lurking within this game and ruin the experience. All it takes is being faced with the unknown for a game to be scary, no matter the genre, Voices of the Void knows this well. Go check it out, and thanks for reading!